| Home; Aviation; Cameras; Fiction; Health&Safety; Military; MS-Apps; Non-Fiction; Submarine; Technical; Trains; Watches; Transportation |

|---|

Lockheed D-21 Mach 3 UAV

Courtesy Greg Goebel, vectorsite.net and Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Edited by David Barth 30 April 2012.

LOCKHEED D-21 TAGBOARD

In the early 1960s, Lockheed had developed the Mach 3 "A-12" spyplane, which quickly evolved into the famous "SR-71 Blackbird" strategic reconnaissance aircraft. After the destruction of Francis Gary Powers' U-2 over the USSR in 1960, concepts for an A-12 drone were proposed. Kelly Johnson, in charge of Lockheed's secret "Skunk Works" that had built the A-12, thought the A-12 itself would be too big and complicated to make a useful drone, but felt that the design and technology could be leveraged into a smaller ramjet drone that could perform the same mission. The drone could be launched by the A-12, it being one of the few aircraft fast enough to allow the drone's ramjet engine to light up properly.

The ideas congealed into a formal study for a high-speed, high-altitude drone begun in October 1962. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) the agency tasked with control over all stategic reconnaissance systems including satellites, and a subsidiary of the National Security Agency (NSA), backed the idea, with funding scraped up for initial development. The drone itself was given the preliminary designation of "Q-12", and was a very deep secret.

Kelly Johnson wanted to power the Q-12 with a ramjet built by Marquardt for the Boeing BOMARC long-range Surface-to-Air-Missile (SAM). Marquardt's plant was close to Lockheed's, helping ensure security, and the two companies had collaborated on several programs in the past. Conversations with Marquardt engineers indicated the BOMARC ramjet could be used, though the engine, ultimately designated the RJ43-MA-11, needed some work, since it wasn't designed to burn for much longer than it took a BOMARC to hit a target a few hundred kilometers away. The Q-12's engine had to operate for at least an hour and a half, much longer than any ramjet built to that time.

In order to reduce weight and cost, the Q-12 was not designed to be recoverable. Instead, it would eject its nose section, containing the camera payload and the expensive guidance system. The nose section would descend by parachute for recovery.

A mockup of the Q-12 was ready by 7 December 1962. Radar tests indicated that it had an extremely low radar cross section. Wind tunnel tests also indicated the design was on the right track. The CIA was not enthusiastic about the Q-12 at first, mostly because the agency was overextended at the time with U-2 missions, getting the A-12 up to speed, and covert operations in Southeast Asia.

In contrast, the Air Force was interested in the Q-12 as both a reconnaissance platform and a cruise missile, and the CIA finally decided to work with the USAF to develop the new drone. Lockheed was awarded a contract in March 1963 for full-scale development of the Q-12.

The major initial problem confronted by the design engineers was launch of the Q-12 from the A-12 mother ship. The Q-12 was to be carried on the back of the A-12, with an uncomfortably small amount of clearance between the A-12's fins, and the potential for disaster during separation of the drone from the mother ship was obvious.

The design was finalized in October 1963, and the designations were changed. The drone was now known as the "D-21", while the A-12 launch aircraft was known as the "M-21". "M" stood for "Mother" and "D" stood for "Daughter". The project now had the codename "Tagboard".

The production UAV, the "D-21A", looked like a stovepipe with a cone in its inlet, with a tailfin and wings running the length of the stovepipe that gave the drone something of the look of a sweptback manta ray. It was mostly made of titanium, with some elements made from radar-absorbing plastic composites.

| LOCKHEED D-21A SPECIFICATIONS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Specification | Metric | English |

| wingspan | 5.8 meters | 19 feet |

| length | 13 meters | 42 feet 10 inches |

| launch weight | 5,000 kilograms | 11,000 pounds |

| maximum speed | 4,300 KPH | 2,700 MPH / 2,300 KT |

| service ceiling | 29,000 meters | 95,000 feet |

| range | > 5,550 KM | > 3,450 MI / 3,000 NMI |

The reconnaissance payload and guidance systems were carried in a "Q-bay" about 1.9 meters (six feet) long. These systems were built into a module that plugged neatly into the bay and was known as a "hatch". As per the original design concept, the hatch would be ejected at the end of the mission, and the aircraft would then blow itself up with a self-destruct charge. The hatch would be snagged out of the air by a C-130 Hercules, a technique that had been refined by the Air Force to recover film canisters from reconnaissance satellites.

The M-21 was a two-seat version of the A-12, with a pylon on the fuselage centerline between the tailfins to carry the drone in a nose-up attitude. A periscope allowed the back-seater, or "Launch Control Officer (LCO)", to keep an eye on the D-21. Two M-21s were built, along with an initial batch of seven D-21s for test flights.

The first flight of the M-21 and D-21 combination was on 22 December 1964. The D-21 remained attached to the M-21 throughout the flight, since it was simply to study aerodynamics and other systems issues. Refining the scheme until an actual release proved troublesome, and the first launch was not until 5 March 1966.

The release was successful, though the drone hovered above the back of the M-21 for a few seconds, which seemed to one of the flight crew like "two hours". Kelly Johnson called it "the most dangerous maneuver we have ever been involved in, in any airplane I have ever worked on." The D-21 itself crashed after a flight of a few hundred kilometers.

This was still not too bad for the first flight of such an advanced machine, but the CIA and the Air Force remained unenthusiastic about the program. Kelly Johnson conferred with Air Force officials to see what he could do to tune the project more closely to the service's needs. Among other things, Johnson suggested launching the D-21 from a B-52 bomber and using a solid rocket booster to get the drone up to speed.

A second successful launch took place on 27 April 1966, with the D-21 reaching its operational altitude of 27,400 meters (90,000 feet) and speed of Mach 3.3, though it was lost due to a system failure after a flight of over 2,200 kilometers (2,200 NMI). This was regarded as very satisfactory progress. The successful tests sharpened the interest of the program's government backers, and by the end of the month a contract for 15 more D-21s had been placed.

A third successful flight took place on 16 June 1966, with the D-21 flying through its complete mission, though the hatch wasn't released due to an electronics failure. However, a launch attempt on 30 July 1966 ended in disaster. The D-21 collided with the M-21 on release, destroying both aircraft. The two crewmen ejected and landed at sea. The pilot, Bill Park, survived, but the LCO, Ray Torick, drowned when his pressure suit leaked.

All the fears about launching the D-21 from an A-12 had been proven justified, and Kelly Johnson immediately canceled any more launches from the M-21. However, he felt that the B-52 launch scheme was still practical, and the D-21 program remained alive and well, being re-codenamed "SENIOR BOWL".

Adapting the D-21 for launch from a B-52 was not trivial. The drones had to be broken down, modified, and reassembled to allow fitting the attachment points on top to link the drone to the B-52's pylon and the points on the bottom to link the drone to its solid-rocket booster. The modified drone was designated the "D-21B".

The booster was no little RATO pack: it was a solid-fuel rocket with a length of 13.5 meters (44 feet 4 inches) and a weight of 6.025 tons (13,290 pounds), making it longer and heavier than the drone itself. The booster had a single, small tailfin on the bottom to ensure that it flew straight. The tailfin folded to allow for ground clearance when the B-52 was not flying. The booster had a burn time of about a minute and a half, and a thrust of 121.4 kN (12,380 kgp / 27,300 lbf).

Two B-52Hs were modified to launch the D-21Bs. B-52 modifications:

- The B-52s were given two large underwing pylons to carry the drones, replacing the smaller pylons used for the B-52's Hound Dog cruise missiles.

- Two independent Launch Control Officer (LCO) stations were added at the rear of the bomber's flight deck to monitor the launch and provide a way to destruct the drone after launch, if necessary.

- Command and telemetry systems were added.

- A celestial navigation system was installed to accurately identify the B-52's position at launch.

- A temperature control system was added to keep each drone at a stable temperature before launch.

First attempted launch of a D-21B was on 28 September 1967, but the drone accidentally fell off the B-52's pylon. Its booster lit, but the D-21B went straight into the ground. Kelly Johnson called the incident "very embarrassing."

Three more launches were performed from November 1967 through January 1968. None were completely successful, so Johnson ordered his team to conduct a thorough review before renewing launch attempts. The next launch was on 30 April 1968, and was also a failure.

The Lockheed engineers went back to the drawing board once more, and on 16 June 1968 they were rewarded with a completely successful flight. The D-21B flew a test mission at the specified altitude and course over its full range, with the hatch recovered successfully, though it didn't have a camera payload.

The troubles were not over yet, however. The next two launches were failures, followed by another successful flight in December. A launch near Hawaii in February 1969 to simulate an actual operational flight was a failure as well, but the next two flights, in May and July, were both successes.

Tagboard now appeared ready for operational flights. The first operational mission, part of a program designated "Senior Bowl", was on 9 November 1969, with a D-21B sent to observe China's Lop Nor nuclear test facility.

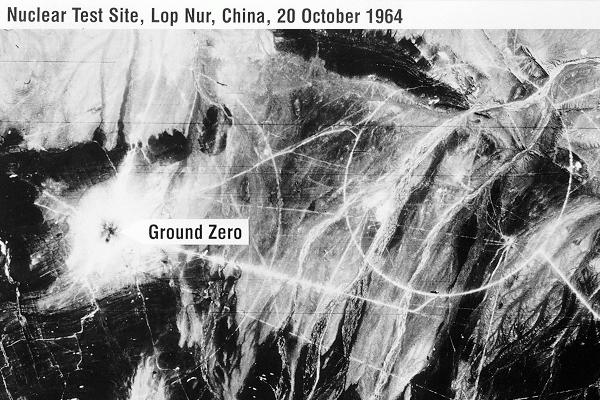

US satellite intelligence imagery of 6-9 August 1964 showed that the previously suspect facility near Lop Nor in Sinkiang was almost certainly a nuclear testing site. Developments at the facility include a ground scar forming about 60 percent of a circle 19,600 feet in diameter around a 325-foot tower (first seen in an April 1964 photograph), and work on bunkers near the tower and instrumentation sites at appropriate locations were under construction. The outward appearance and apparent rate of construction indicated that the site could be ready for a test in two months or so. The characteristics of the site suggested that it was being prepared for both diagnostic and weapon effect experiments.

In October 1964 China joined the nuclear club by conducting its initial atomic test at Lop Nor, in western China. This was the prelude to a series of increasingly sophisticated test shots which continued up to 1996. All known Chinese nuclear weapons tests were conducted at the Lop Nor Test site.

|

| Nuclear Test Site at Lop Nor (aka Lop Nur), China, 20 October 1964, taken by a KH-4 Corona Reconnaissance Satellite. |

The Chinese never spotted the stealthy drone which disappeared and was not recovered. Once again, the Lockheed engineers went back to the drawing board. Another test flight was conducted on 20 February 1970, and was successful. However, the next operational mission was not until 16 December 1970. The D-21B made it all the way to Lop Nor and back to the recovery point, but though the hatch was dropped as planned, it did not deploy its parachute and was destroyed on impact.

The third operational flight, on 4 March 1971, was even more frustrating. Once again, the D-21B made it all the way to Lop Nor and back again, and properly discarded the hatch. The hatch actually deployed its parachute, but the midair recovery failed, and a destroyer that tried to pick the hatch out of the sea ran it down. The hatch sank and was lost.

The fourth, and as it turned out last, flight of the D-21B was on 20 March 1971. It was lost over China on the outbound leg, apparently having been shot down. In July, the D-21B program was canceled, Although the program had suffered from more than its fair share of bugs, it appears the main reasons were the same as those that led to the cancellation of the Model 154 Firefly: Nixon's rapprochement with China and operational introduction of the Big Bird (KH-11) reconnaissance satellite.

When Ben Rich, Kelly Johnson's successor at the Skunk Works, visited Russia in the 1990s after the fall of the USSR, a contact gave him a package that contained parts of the D-21 that had disappeared on the first operational flight. It had crashed in Siberia. The Soviets had apparently been puzzled as to what it was, but it appears that they also obtained the wreckage of the D-21 lost on the fourth operational flight. The Tupolev design bureau reverse-engineered the wreck and came up with plans for a Soviet copy, named the "Voron (Raven)", but it was never built.

38 D-21s were built, with 21 expended. The other 17 were put in mothballs at the Davis-Montham Air Force Base "boneyard" near Tucson, Arizona. Since the base was open to the public, the exotic D-21s were eventually spotted and photographed, leading to wild speculations as to their nature that were inflamed by misinformation generated by the Air Force.

For example, they were described as test machines used in development of the A-12 / SR-71. The full details didn't come out until 1993, when an author named Jay Miller published a book titled LOCKHEED'S SKUNK WORKS: THE FIRST 50 YEARS that gave a reasonably complete account of the D-21 project. The mothballed drones were passed off to the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA), which took four, and to a number of air museums.

In the late 1990s, NASA considered using their D-21s to test a hybrid "rocket-based combined cycle (RBCC)" engine, which operates as a ramjet or rocket, depending on its flight regime. However, this idea was abandoned, with NASA preferring to use a derivative of the agency's X-43A hypersonic test vehicle for the experiments.

The Seattle Museum of Flight was one of the museums that received a D-21. The museum also had an A-12 (M-21), and museum volunteers built a pylon to allow mounting a D-21 on its back. The combination is the central exhibit in the main display area and is one of the most spectacular sights available at any air museum.

|

| Lockheed D-21 UAV mounted on an SR-71 at the Boeing Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington, USA. |

|

| Lockheed D-21 UAV mounted on a dolly. |

|

| Lockheed D-21 mounted on an M-21. |

|

| Rear view of a Lockheed D-21. |

|

| M-21 in flight with a Lockheed D-21. |

|

| Boeing B-52 carrying two D-21s with their boosters. |

|

| Close-up of B-52 carrying a D-21 and its booster. |